Baumol vs Wright

The push and pull of prices in an industrialized economy

In a modern, industrialized economy there are two opposing forces: Baumol’s Cost Disease and Wright’s law. Together, they determine the price levels in an economy and therefore what type of economic activity will be most likely to occur. Broadly speaking there are two types of industries: those in which labor is an input to the product and those in which labor is the product. They can also be thought of as those which benefit from economies of scale and those that do not. Manufacturing is a great example of the former; yes there are engineers, technicians, and operators that all work in factories, but the customer is buying the finished product, not the labor. Education or healthcare would be an example of the latter; the service is the product. Class sizes are usually seen as a contrary indicator to the quality of a school and a medical procedure of a doctor’s appointment is the primary reason for which one consumes healthcare.

Productive industries, like manufacturing, natural resource extraction, agriculture, etc, generally benefit from new technology. It is more efficient to use a self driving tractor to plow a field than it is to use a horse and a plow. This results in fewer man-hours required for the same amount of output and lowers the final price of the product.

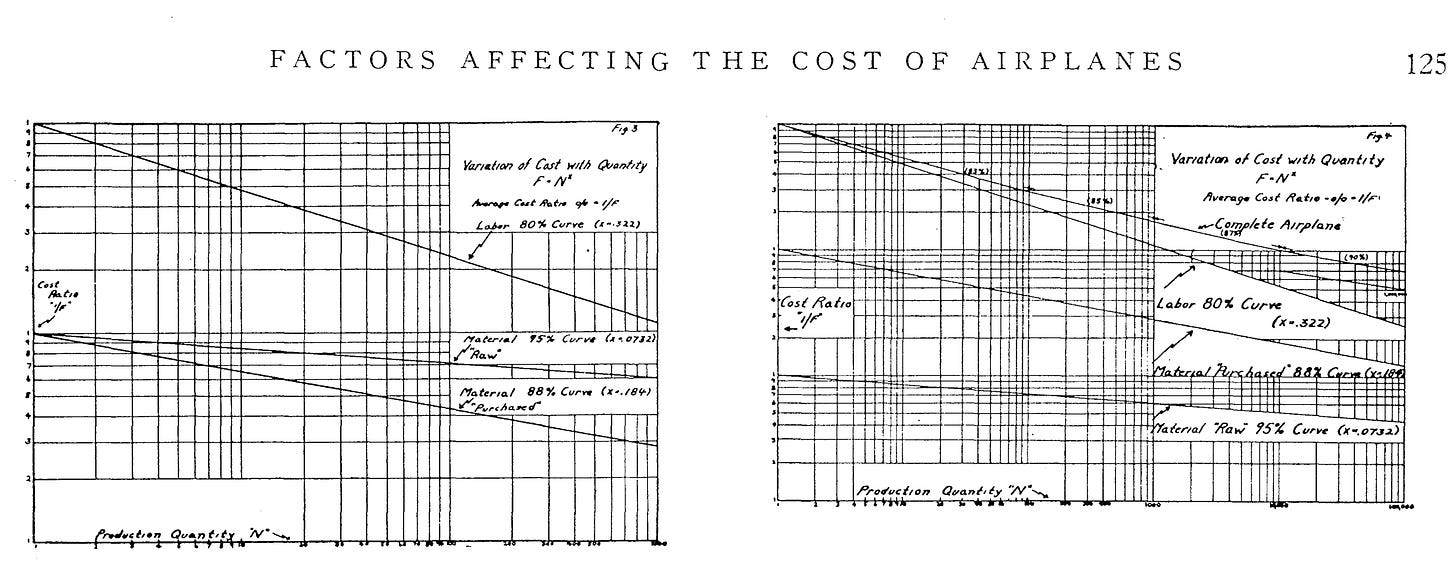

For manufacturing, there is a specific relationship that was noticed by a manufacturing engineer in the 1930s. Theodore Wright noticed that when the number of aircraft manufactured double, the marginal cost of each aircraft decreased exponentially. This is called ‘Wright’s Law” and it generalizes to pretty much all manufacturing goods. When plotted in log-log space, the relationship between quantity produced and marginal cost is a straight line. The slope of this line will differ depending on what the good is, but this relationship holds across a variety of manufactured goods. This economic effect is also sometimes referred to as the “learning curve”. The reasoning is simple. As the manufacturing process gets more mature, it also gets more optimized.

The more units that are produced, the cheaper they get; this is an economic law.

However, things work differently in the non-productive, or service industries. The effect here is nearly the opposite. Because the primary, and in some cases only, input to service-based employment is labor, there are few opportunities to make them more efficient. Think about getting a haircut: would you want your barber to rush or to be more efficient? The economist William Baumol used the example of a string quartet to illustrate this phenomenon. When Beethoven’s String Quartet number 14 was first performed in 1826, it required the same exact amount of labor as it does today. However, because the economy is more advanced, there are many more other things that people spend their time and money on, so when adjusted for inflation, the cost of paying the musicians to play the same Beethoven piece is substantially more expensive now than it was when the piece was first performed. By one estimate, the piece is 23 times more expensive to perform now.

The economic reasoning behind this phenomenon is a concept called “cross-elasticity of demand”. The musicians that perform the Beethoven string quartet need to find a place to live, they need to pay for food, they need to pay for healthcare, they need to pay for childcare and education and all the other necessities of life. All of the other people that live in the same area as the musicians also need to pay for those same things, so, in order for the musicians to make the decision to pursue a career in music, the wages must be enough to afford the basic necessities of life. Because the price of rent, education, healthcare, childcare, etc are determined by the market, the aggregate supply and demand for those goods and services by others in the economy, the wage demanded by the musicians will be roughly in line with the wages offered in other sectors of the economy, regardless of the cost and revenue structure associated with that industry.

And this is where the idea of cost “disease” makes sense. Because of Wright’s law, we know that manufactured goods, and the output of productive industries more generally, drives costs down. However, because the people employed by these productive industries are competing in markets such as housing, education, healthcare, childcare, etc etc, with those who work in industries that do not benefit from economies of scale, the economic efficiencies associated with decreasing marginal costs are gobbled up by the rising cost of labor associated with services. The end result is an increase in price levels across the whole economy. In effect, the productive sectors of the economy subsidize wage gains with the unproductive parts of the US economy.

Wright’s Law and Baumol’s Cost Disease together act as a push and pull for price levels in an economy. If the economy is biased towards productive industries, things will get cheaper, if the economy is biased towards services, things will get more expensive. The economist Victor Fuchs, noted the productive industries to service industries transition happening in the US economy in the late 1960s and early 1970s. 1971 is often referenced as the year that this transition occurred and the rapid rise in price levels, service based employment, change in asset prices can be seen.

https://wtfhappenedin1971.com/

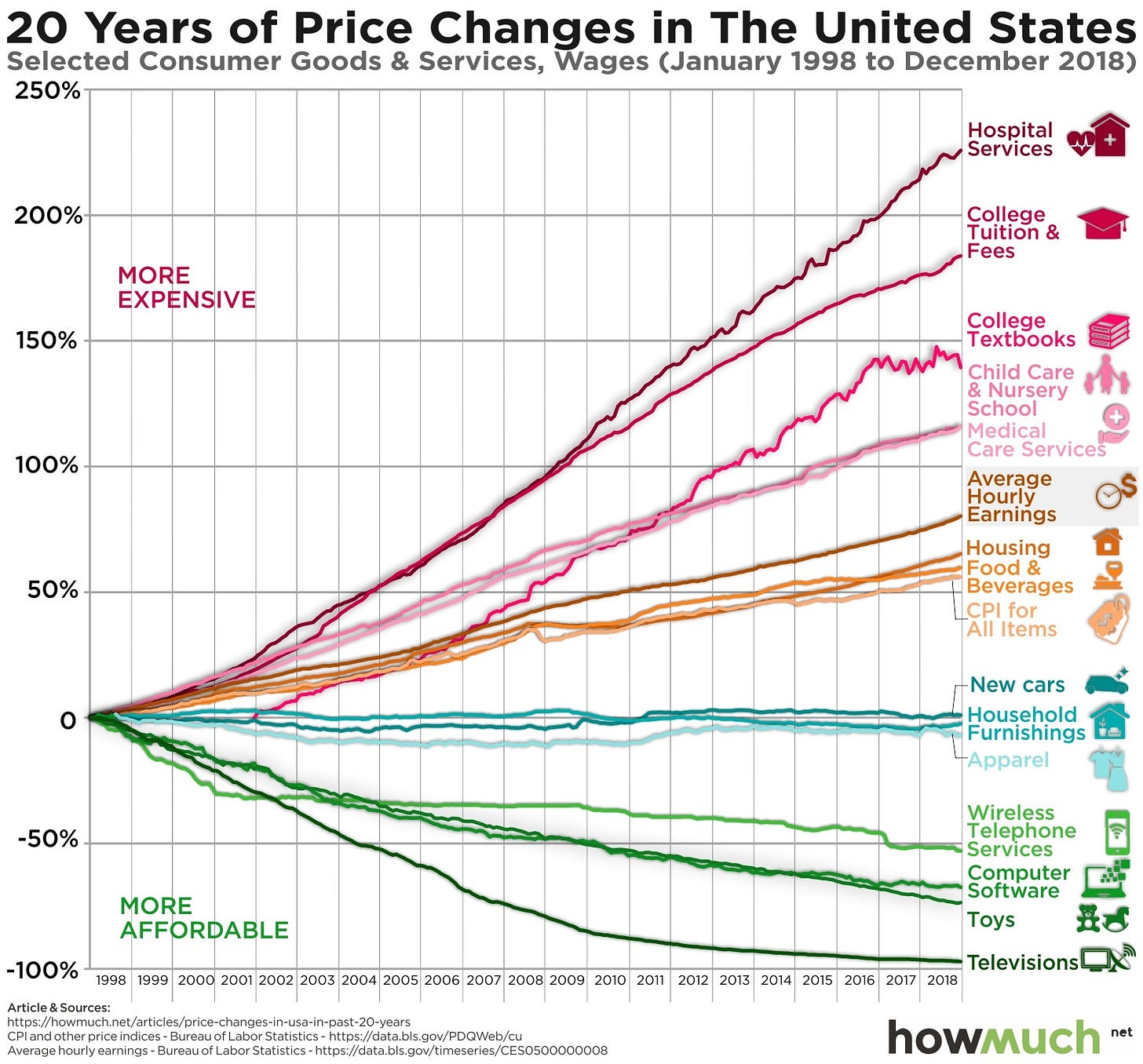

There are often diagrams that show the relative cost of things over time like the one below. Analyzing this diagram in terms of Wright’s Law and Baumol’s Cost Disease is a very straightforward exercise.

If you look at the items that rise faster than wages, they are all labor-intensive services that cannot easily be scaled like education, healthcare, childcare, etc. If you look at the things below the curve they are all manufactured goods that benefit from economies of scale. As predicted, the cross elasticity of demand makes services more expensive, even as goods get cheaper.

Furthermore, there is a bit of game theory for those choosing careers. Knowing (or intuiting) that working in a service-based industry will always yield a wage that will keep up with cost of living without having to face the steep competition associated with high capital expenditure, low margin industries like manufacturing can nudge intelligent motivated, ambitious people into careers that are financially rewarding but do not lower price levels for the economy as a whole. This is the classic setup of a coordination problem in which the choice that is better (or less bad) for each individual actor is not the same as what is best for the society as a whole.

So what can we do about this? What, if anything, can be done? The field of economics earned the title “the dismal science” honestly; unfortunately these seem to be phenomena associated with economies that become progressively more service oriented, like the United States. I don’t see an easy way out of the cost spiral associated with Baumol’s Cost Disease. Both Fuchs and Baumol were not optimistic that there would be a way to unwind the costs associated with these phenomena. The best thing that we can do is to understand their causes and effects.

The competing forces between Baumol’s cost disease and Wright’s law have an incredible amount of explanatory power and are powerful tools for economic analysis. Together, these two principles serve as the basis for my ideas on industrialization and the role of services in an economy. In posts to come, I’ll be making heavy use of these two ideas so I thought it would be best to introduce them in a separate post.

Sources:

https://pdodds.w3.uvm.edu/research/papers/others/1936/wright1936a.pdf

https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w0486/w0486.pdf

https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c1155/c1155.pdf

https://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~wbaumol/OnThePerformingArtsTheAnatomyOfTheirEcoProbs.pdf

Love this frame—Baumol vs. Wright is such a clean way to see the tension.

I took the Baumol side for a spin with a violinist, a plumber, and a toilet that costs more than it should.

https://foundandfiled.substack.com/p/entry-4-the-violinist-and-the-toilet